The Myth of Modular Units

Noah Demarest AIA, ASLA, LEED AP, CNU

Principal

STREAM Collaborative

There is a myth that has been perpetuated in design schools, trade schools, home improvement magazines, TV shows, and online that building in even units of dimension is easier, more cost-effective and conserves material resources. This is partly right but mostly wrong.

Sheet goods are commonly used in all kinds of building. Plywood made of layers of cellulose glued together to create a product that is more dimensionally stable and in some ways stronger than wood itself was patented in the late 1700’s but it wasn’t until 1928 that the first 4’x8’ sheet of plywood was commercially available. So that makes the use of modular sheet goods a thoroughly modern building practice. For better or worse, the Modernists who made great use of modularity in their designs touted the benefits of industrial efficiencies and promoted this theory that working within the constraints of modular building materials is a more efficient and cost-effective way to build for the masses. I’m not sure that really ever worked out the way they envisioned. Perhaps the modern movement was just ahead of its time as it has only been in recent years (more than 100 years after the dawn of modernism) that CNC routers and 3D printers are beginning to make their way into the construction of homes and buildings of all types. With the use of these cutting-edge technologies (pun fully intended) and post-industrial recycling the whole concept of waste goes away and so does some of the role and responsibility of the designer to plan for modularity as that goal is easily handled through computer-controlled machines.

For masonry work, it makes a lot more sense to figure out the coursing as it relates to openings to make everything fit with the least amount of cutting. But for wood construction, it just isn’t that big of a deal. When you have a brick veneer on a wood frame building it becomes completely impossible to reconcile the two without compromising the optimal modularity of one or the other.

If you can make the dimensions work out for a design, without bending over backwards or losing other desired features, then it is more efficient for time, energy, and materials to build to a standard unit size, like using a 2-foot increment for your framing layout because sheathing comes in 4’x8’ sheets. Where this breaks down is after you are done sheathing when nothing else works out to be a perfect 2-foot increment. And how do you actually start your building layout to end up with perfect 2-foot increments for your sheathing? Do you plan for your stud walls to be ½” less to accommodate the thickness of the sheathing when they overlap at the corners?

Assume the interior is one big room, which it usually isn’t; the drywall goes to the inside corners of the framing, so that will never be a dimension divisible by 2 feet if you planned for the exterior to be divisible by 2 feet. If you are using a panelized siding product applied over a ¾” furring strip so you have a proper drain plane, then the exterior wall will be slightly larger than the 2-foot increment of the sheathing. Much of the exterior trim that runs from corner to corner, like a water table or belly band, is also pushed over that 2-foot increment by the furring.

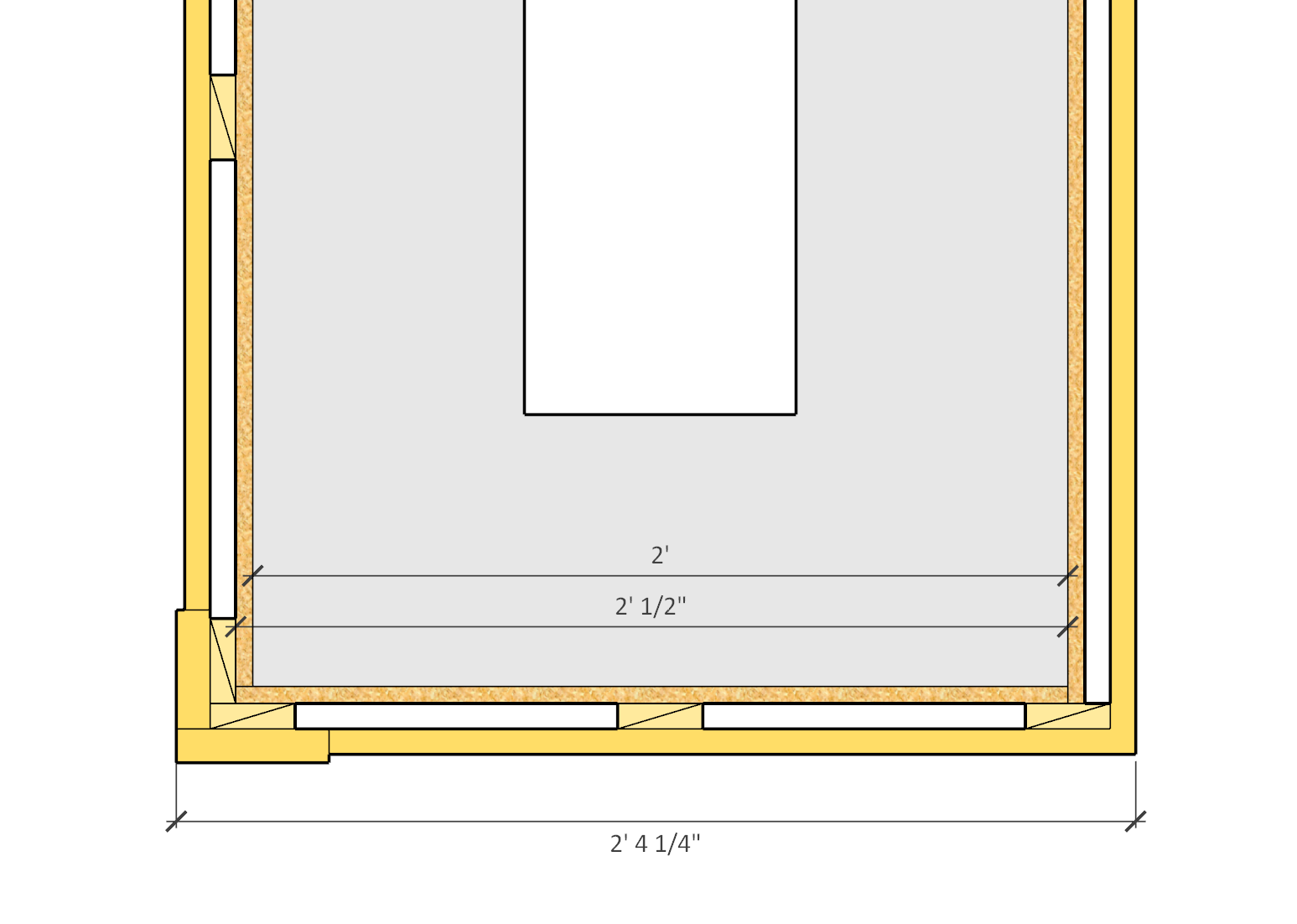

In the image above of a hypothetical plan, the foundation was set at 2 feet (but could be 20 feet) and the plywood corners are butted together to wrap over the foundation meaning your plywood needs to be at least ½” longer or up to 1” longer than the standard 2-foot module. Should we have made our foundation 1’-11 ½” instead? I’m not sure it would be worth the trouble.

There are places in construction that work well for standard dimensions, like pre-cut studs to create 8’ 1-1/8” wall plate heights to setup using ⅝” gypsum board on the ceiling and full 8-foot high wallboard and a gap at the floor for prying the sheet up with your foot. Or, designing your foundation to increments of standard concrete formwork because they come in fixed dimensions. We should make the initial layout of the foundation as easy as we possibly can because having nice rational numbers on the foundation drawing sets the stage for the rest of the build.

But ingrained into good building practice is wiggle room. Wiggle room is an often overlooked detail that many designs could utilize better, in the name of efficient use of materials. This gets us back to the 2-foot increment layout. As we all know, the real world does not always work out as well as those of us in the design world would like to see. So, for whatever reason, what if the sheathing doesn’t quite work out? Best case, you are trimming a ½” strip off of your last sheet. Worst case, you are ½” shy on your last sheet of sheathing. Hopefully, you can still barely nail the sheet onto the framing, but wouldn’t it have been nice to have a little bit of wiggle room?

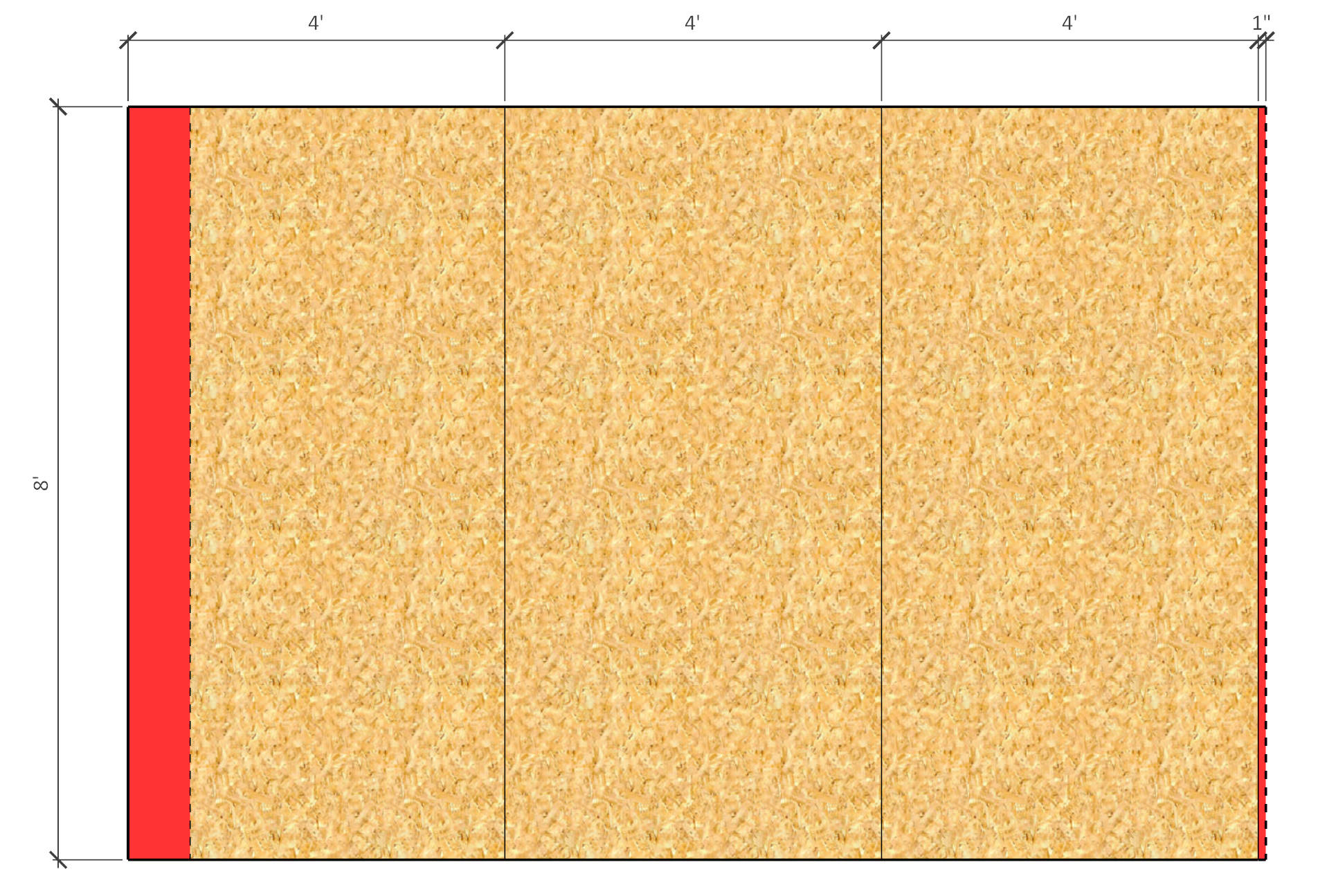

In the image above, I would much rather live with trimming the 6” on the left as waste than to attempt to be perfect and end up having to cut an extra 1” off an entire sheet that otherwise wouldn’t be needed as shown on the right.

There is a certain beauty of a design that fits all the required features into a compact space with almost no waste, but wiggle room is nice to have. Giving stairs a width of 38” instead of the code required 36” would give enough wiggle room to still be compliant, in case a foundation wall is off from its dimension by ½” or cumulative rounding errors add up to more than 1 inch across the length of a long building (which isn’t uncommon). But for some reason, it is rare to see a width bigger than 36” on stairs in a budget-friendly residential project and as designers, we are just setting up our builders with more challenges, all in the name of being efficient.

By the way, a good builder will manage the waste on the project regardless of the efforts of the designer to meet this myth of modular units. Every little piece of scrap will either be used somewhere on the job, or end up in the back of someone’s pickup (to be used as kindling or in a tree fort at home), but it rarely goes straight to the dump. When LEED first came out with a credit to recognize projects that limited their construction waste it was assumed that there was this massive problem in the industry that needed to be rectified. However, in my experience, most builders easily meet the LEED credit and they always have and always will.

I am all for smart planning and conservation of materials, but I think a little wiggle room is more important than worrying about achieving the mythical modular layout.